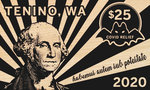

Tenino’s response to the pandemic — widely-publicized wooden scrip similar to money that was distributed to residents — may soon be enshrined in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Earlier this month, a curator of the museum reached out to the small town asking to display some of the wooden currency, which was aimed at helping keep the local economy afloat during a global emergency.

“It’s still kind of surreal,” Mayor Wayne Fournier said Friday, noting that other museums have also been reaching out regarding the unique scrip program. “But nothing to the level of the Smithsonian, you know? The Smithsonian, that’s America’s museum.”

The Smithsonian has already chronicled Tenino’s wooden scrip program from nine decades ago. As far as Fournier knows, 2020 was the first time a local government had spearheaded a scrip program. But during the Great Depression, Tenino’s chamber of commerce ignited a similar program. So when the pandemic hit, Fournier said, Tenino simply had to “dust that idea off.”

Printing hyper-local currency, he contended, is part of the town’s “myth and lure.” The scrip program, then, is just the next chapter in the town’s numismatic history — all to be preserved in the world’s largest museum complex.

Hearing from the Smithsonian is exuberating, but Tenino has been getting love from more than one prestigious institution during the course of the pandemic.

The town has already given some wooden tokens to two other museums — one in New York and the other in Canada. And Fournier was invited to partake in Temple University's “The Critical Dialogue” lecture series to discuss monetary theory. He’s also been talking to grad students in California who are studying micro-currency concepts.

“And the nation of Japan contacted us to get permission to put our story in their civics textbook,” Fournier added. “It’s outrageous.”

Turns out, Tenino’s small, wooden tokens — valued by the city at $25 each — fit into a larger conversation around economics, monetary infrastructure and other high-level concepts.

“I think there’s different layers to the idea. The very basic thing is just ‘what is money?’ and the monetary theory side of it,” Fournier said. “And you can talk about it through the lens of decentralizing your infrastructure, and how if you have a large centralized system, it’s dangerous … if you decentralize your system and kind of push authority down it makes a stronger system. A little more chaotic, but it’s more resilient.”

On the ground, though, perhaps the biggest takeaway from Tenino’s second wooden money experiment is just how successful it was. Printing the money — which features a stylish George Washington design created by local artist Adam Barr — cost the city only $300. And although the plan was to have residents return the tokens to get reimbursed $25, almost none of the wooden money made it back to the city.

Instead, many residents held on to the wooden pieces, some partaking in what Fournier called a “grey market” online. Fournier and his coworkers have seen the pieces go for hundreds of dollars.

That’s good news for the city. While not having to shell out much money to residents, Tenino was simultaneously receiving donations from around the world to support their program.

When asked if monetary theory is something he’s interested in pursuing, Fournier said he’s unsure. He would love to do a Ted Talk, although he acknowledged that the Smithsonian is perhaps a more prestigious honor.

“The Smithsonian. I don’t know how it can get any better than that,” Fournier said, laughing. “It’s all downhill from here for me.”