“History is so darned messy.”

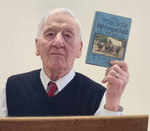

So says Raymond J. Egan, of Steilacoom, a historian and reenactor who portrays legendary Northwest pioneers such as Ezra Meeker, Father Luigi Rossi and others. He presented an informative and entertaining three-part program Sunday afternoon for the Toledo Historical Society at Steamboat Landing in Toledo.

Egan handed out enlarged, laminated photos showing Meeker on March 12, 1906, in The Dalles, Oregon, where he read a proclamation dedicating a marker that states “End of the Old Oregon,” even though the trail officially ended at Oregon City, according to Congress.

But, Egan noted, “The end of the trail was really wherever you went. As a matter of fact, if you were to draw a picture of the Oregon Trail, the easiest way of describing it would be a piece of rope frayed at both ends — a number of places they started and hundreds of places they finished.”

He didn’t know why the marker listed the start date of 1843, but 1906 was when Meeker dedicated it.

The photo showed Meeker with a 1,430-pound farm wagon he used to retrace the Oregon Trail in 1906 all the way to New York. The wagon, which he said is stored at the Washington State Historical Society, was exactly like those that carried thousands of pioneers across the country to Oregon Territory in the mid-19th century — typically 10 feet long, 4 feet wide and 4 feet high with floors sloped toward the center so cargo would lean inward as the wagon rocked.

On the left in the photo stands 7-year-old Twist, an “ox” — defined as a neutered male bovine of any breed over four years of age trained to work. On the right is Dave, a 5-year-old steer purchased only weeks earlier from a Tacoma stockyard.

During a stop in Tenino, Meeker wrote in his journal, “Dave is still not an oxen.”

Each beast weighed about 1,400 pounds. Today, more than a century later, Egan said, oxen weigh about 3,000 pounds each.

Dave had an attitude and kicked Meeker so hard at Baker City, Oregon, he was lame for a month, Egan said. In fact, Meeker’s favorite companion, a Scotch collie named Jim, hated Dave, and at one point, the steer kicked the dog off a bridge.

Meeker was kind of a braggart, Egan said, but a prolific writer who chronicled the pioneer journey in nine books. Pioneers needed to clear dust and debris from their oxen’s nostrils to prevent overheating or the air-cooled animals that didn’t sweat could die, Egan said. The oxen needed horns to keep the yoke from sliding over their heads. The preferred breed was a Milking Red Devon, Egan said, and oxen were preferable to horses because they’d eat anything.

To save their animals’ strength, pioneers seldom rode inside the wagons with heavy iron wheels that thumped over rocks.

“You didn’t ride in that wagon by choice,” Egan said. “Those who were too ill to walk and had to ride in a wagon tried to get well in a hurry. One traveler said that the longer she rode in the wagon, the more attractive death became.”

Pioneers ate a hearty breakfast of beans and hardtack before pulling out each day at about 5 a.m. They stopped for “nooning” and continued until camping for the night. Oxen traveled about two miles an hour, so they usually covered 17 miles a day.

During the second part of his program, Egan cleared up misconceptions about expressions used by early pioneers in nearly 2,000 diaries and journals written along the trail and preserved by the Oregon-California Trails Association. Others wrote memoirs later in life that are stored at the Washington and Oregon State Historical Archives.

The pioneers never spoke of crossing the Oregon Trail, Egan said, but instead referred to their journey as “when we crossed the plains.”

Meeker titled his 1906 book “The Ox Team or the Old Oregon Trail, 1852–1906” and frequently referred to the Oregon Trail in his other volumes and thousands of speeches across the country.

Wagon train leaders often gave themselves titles such as captain or colonel and kept those monikers, Egan said, referring to a headstone in Tumwater’s Masonic cemetery for Colonel Michael T. Simmons.

Words and their meanings change throughout time, Egan said. Pioneers often referred to their traveling companions as their “party,” which his 1860s dictionary defined as “a number of persons united by some tie” rather than today’s meaning of “a social gathering.”

Many diaries used the word “tolerable,” a favorite expression, and “perfect” and “first class” and “first rate.” If something works, Egan said, it “answers the purpose.”

Meeker described his loving bride as “the most buxom girl in Indiana.”

“Well, in the 1850s and 1860s, my dictionary said that buxom meant ‘smiling, lively, healthy,” Egan said. “When it became Dolly Parton ...”

Laughter greeted his comment.

Pioneers often stated, “we’ve seen the elephant,” which Egan said referred to having endured trying times such as tipping wagons and dire circumstances. “In other words, we’ve done it all — enough already.”

Philosopher and novelist George Santayana famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it,” but Egan referenced one of the author’s lesser-known statements: “History is always written wrong, and so always needs to be rewritten.”

During the third part of his presentation, Egan spoke about the 1853 Longmire-Biles Wagon Train, when James Longmire and James Biles combined their two trains near the Columbia River to travel north and cross what they believed would be a passable road through Naches Pass to reach the Puget Sound.

The shortcut’s purpose was to cut two weeks from their arduous journey. Another part of the goal, Meeker said, was to divert a part of the expected emigration which would otherwise go to Oregon and be lost to the new but yet unorganized territory of Washington.

But the nearly two dozen workers who spent two months clearing the path on the west side and the 11 toiling a month from the east hadn’t finished the road through dense old-growth forests. And how the company reached the summit and lowered wagons and oxen down a 33-degree slope became a heated topic of debate.

A well-respected Oregonian, George Henry Himes, who was nine when he and his family crossed Naches Pass, was the first curator of the Oregon Historical Society, a position he held for four decades. He wrote a lengthy letter to Meeker on Jan. 23, 1905, detailing a traumatic story at Naches Pass in October 1853.

“For a sheer 30 feet or more, there was an almost perpendicular bluff and the only way to go forward was by that way,” Himes wrote, describing their search for alternate routes. “So the longest rope in the company was stretched down the cliff, leaving just enough to be used twice around a small tree, which stood on the brink of the precipice, but it was found to be altogether too short. Then James Biles said, kill one of the poorest of my steers and make his hide into a rope and attach it to the one you have. Three animals were slaughtered before a rope could be secured long enough to let the wagons down to a point where they would stand up. There were 36 wagons belonging to the company, but two of them with a small quantity of provisions were wrecked on this hill.”

Meeker published the entire letter and referred to it so often that it became legend, lore and the story posted on a weathered sign erected by a Boy Scout troop in 1980.

But Egan doesn’t believe it.

Several adults with the Longmire-Biles Train disputed Himes’ account, saying the company had enough rope to lower the wagons and never slaughtered any oxen. James Longmire wrote the pioneers spliced ropes in preparation for the steep descent, tied one end to each wagon axis and the other to a large tree, and lowered the wagons slowly a distance of 300 yards. Longmire said only one wagon crashed to the bottom after the rope frayed.

“Well, we may infer from the copious description then that there was sufficient rope on hand to lower the wagons one at a time a distance of some 300 yards, totally contradicting Himes,” Egan said.

Another pioneer, Van Ogle, disputed Himes’ account in a story published in the October 1922 Washington Historical Quarterly. “There were no oxen killed for skins at all,” he said. “I was 28 years old, and I saw everything that was going on.”

Egan tends to believe the adults and explained why.

Even Himes acknowledged the existence of more rope by saying they used “the longest rope in the company,” so Egan asked, why would they need to slaughter oxen for hides rather than using the other ropes?

And Himes and others mentioned how hungry they were upon reaching the prairies. If they had slaughtered three oxen at the top of the pass — which would have yielded 1,800 pounds of dressed meat, Egan said — why were they hungry?

Egan wondered why Meeker, an astute businessman and respected journalist and author, accepted the Himes’ ox-rope story at face value. Perhaps, Egan suggested, promoting the enticing and bloody tale could increase his book sales, especially important after his hopyards failed. Or Meeker may have been indebted to Himes for contributing money for his efforts to retrace the Oregon Trail and erect historic monuments along the route.

Or perhaps Meeker failed to notice the contradictions in Himes’ story — the longest rope in the company and their hunger pains despite allegedly butchering three oxen.

“It doesn’t matter,” Egan said. California has the Gold Rush. Oregon has the Oregon Trail.

“And what do we have?” he asked. “We have a myth.”

•••

Julie McDonald, a personal historian from Toledo, may be reached at memoirs@chaptersoflife.com.