As World War II tore nations and families apart, two best friends in Washington proudly rose to the challenge and enlisted in the military, but not before making a promise to one another.

William “Bill” James Gray Jr. and James Louvier agreed that if anything were to happen to one of them, the other would take care of his friend’s family.

Louvier returned safely from the war. Gray did not.

On April 16, 1945, just three weeks before the war ended, Gray and the rest of the 391st Fighter Squadron 366th Fighter Group were strafing enemy troops in Lindau, Sachsen-Anhalt, Germany, when his Republic P-47 Thunderbolt plane was damaged and crashed. It was determined that he died on impact, but his body wasn’t recovered. He was 21 years old.

Seventy-two years later, Gray is back in the United States.

On July 14, he will be buried at the Tahoma National Cemetery with full military honors. His remains and James Louvier’s ashes will be laid to rest side by side. James died in 2010 after 64 years of marriage to Gray’s sister, Jeanne, fulfilling his promise to his dearest friend.

Her DNA was used to confirm it was his bone fragments found embedded in a tree at a crash site first identified in 1948 when the area was under occupation by Russian forces. Not until April 2016 — 71 years to the day of the fatal plane crash — were military investigators able to fully excavate the site and recover Gray’s remains.

“What a great way to honor both Bill and Dad! To bury them side by side, best buddies reunited,” said Chehalis resident Jan Bradshaw, the daughter of James and Jeanne Louvier.

Up until January, when Jan and other family members were notified of the discovery, not much was known about Gray and his heroic service in the European theater.

Jan was aware an uncle had died in the war. They knew his plane had reportedly crashed, but aside from that, information was scarce.

The loss was so painful for the family that it was rarely discussed.

“We knew he was lost in the war, but we didn’t talk about it very much,” Jan said. “I just knew he was lost in the war and he was a very special young man … We had only heard rumors … but we never really knew what happened to him. We had no idea they were searching for him.”

In October 1948, investigators with the American Graves Registration Command located the crash site. Serial numbers on machine guns found at the site matched up with Gray’s plane, but his remains were not discovered, according to a press release from the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

The family doesn’t appear to have been notified, and if anyone was, that news was lost to time and a lack of discussion about Gray within the family.

Investigators returned to the area in 2012 while searching for the remains of another service member. That’s when a local resident — likely a descendent of the property owner in 1945 — told them of another site.

“They said, ‘We know someone else is here,’” Jan said. “And they took them to the site.”

His remains — comprised of just 14 fragments, some too scorched to extract DNA for testing — were embedded within a tree where his machine guns had been found decades earlier.

“The tree was what preserved Bill’s remains,” Jan said.

After learning his remains had been recovered in January, Jan began reaching out to her family to learn more about her uncle.

As Jan persisted in her search for information, one of Gray’s sister’s, who was just 3 at the time of his death, mentioned that their mother, Elizabeth Gray, had kept a scrapbook in the home where Jeanne now lives in SeaTac. Jan called her brother, who lived next door, and he located the book tucked away in a closet.

Elizabeth Gray had meticulously saved every letter sent by her son during his time at war, along with photographs of his time abroad that he labeled himself while home on leave.

Taken together, the large, bound book is a time capsule that paints a picture of a man who loved his family dearly and courageously performed service to his country without fear of what might happen to him.

“It’s like you’re mourning someone you never knew but you’ve come to know,” Jan said during an interview with The Chronicle at Sticklin Funeral Chapel in Centralia Friday.

“The difference made by having the book was like night and day. All I knew was he had gone to war and the story was he had been shot down … Reading his letters, it’s like I met this wonderful man.”

Her husband, a local pastor, noted: “It’s helped in the grieving to know more about him. It’s taken this mystery with a lot of questions and painted a fuller picture that helps the family process the grief.”

“It was just so painful they didn’t talk about him much,” he said.

Jeanne Louvier’s memory has faded these days, but she still remembers her brother, who she’s quick to note was “two years and a week” older than she. He was the oldest child of Kirkland residents William J. Gray Sr. and Elizabeth Cooper Gray, who in addition to Jeanne, also had two daughters, Donna Schaller and Diane Clawson, and another son, Dean Gray.

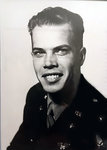

William James Gray Jr., who was known as Bill, was born on Oct. 27, 1923.

“He was very quiet, but very brilliant,” Jeanne said of her brother.

Indeed, he graduated at the top of his class at Franklin High School in 1940 at the age of 16 and enrolled at the University of Washington before later entering Aviation Cadet Training.

As his family wrote in his obituary, “Like many young men and women of his generation, Bill jumped to defend our country, enlisting along with his good buddy and future brother-in-law, James I. Louvier.”

He joined the Army Air Force in September 1942, and was commissioned in March 1944.

He earned the reputation of a man well liked by fellow members of his squadron who was very effective in his job.

An undated newspaper clipping found within the scrapbook details one successful mission:

“Second Lieut. William J. Gray Jr., of Kirkland, P-47 Thunderbolt pilot, and his squadron, so impeded a German panzer advance that a divisional command post and 500,000 gallons of gasoline, prime objective of the recent Von Rundstedt push, were evacuated safely from Butgenbach, Belgium, northern hinge of the German offensive thrust through toward Liege. Report of the bombing and strafing attacks came from headquarters of the Ninth Air Force. Enemy tanks and vehicles were wrecked, the report said, and German troops forced into cover.”

Following his death, a letter sent by Lt. Col. Ansel J. Wheeler included additional details of airborne prowess following his death.

“He is greatly missed by every member of his Squadron as he was extremely popular with officers and enlisted men alike,” he wrote after Gray’s death. “On 11 April 1945, Lt. Gray, in his capacity as flight leader participated in the destruction of several fortified positions and numerous enemy tanks and vehicles near Magdeburg, Germany. Working in close coordination with the ground forces, he skillfully directed an accurate dive-bombing attack on a group of fortified positions; then displaying a high sense of responsibility and tactical awareness, he led his flight in a series of devastating low level strafing attacks on enemy movements in the area. With complete disregard for his personal safety, he braved enemy fire to complete a successful mission. His great courage and deep devotion to duty reflect great credit upon himself and are in keeping with the highest traditions of the Air Forces.”

Other letters tell equally compelling stories of valor, but the scrapbook is largely filled with softer reports from Gray.

Above all, the book shows Gray’s deep devotion to his family.

His letters were addressed to his parents, siblings and friends, and they were sent regularly.

There were frequent requests for food, notes about playing cards with his brothers in arms and occasional details about the plane he was flying. He’d check up on his younger siblings, even questioning Jeanne about who she was dating at the time.

Due to the need for secrecy, he couldn’t include many specifics on his movements, but the restrictions didn’t stop ohim from giving them a look at what he was facing. He’d frequently complain if weather or other factors grounded his plane while the infantry continued fighting.

“Well, I’ve had several missions now and it sure is fun,” he wrote on Nov. 20, 1944. “Sometimes you start sweating though. We are in the Ninth Air Force. It is a tactical Air force, that is, more or less ground support work. In other words we dive bomb and strafe.“

Two weeks before World War II rumbled to a bloody end, Gray ended a letter to his mother with a sobering opinion.

“I still think you people at home are a little too optimistic about the cessation of hostilities over here,” he wrote on April 12, 1945.

Four days later, he was dead, though the family wouldn’t learn of his demise for weeks.

One letter in the book was from KOMO, notifying the family that Gray was being highlighted in a story as a local hero. It was dated May 4, 1945, weeks after his death. Word of his demise had not yet reached home.

A report from the military to his family detailed the fatal crash: “The report reveals that during his mission while making a strafing run over the target, your son’s Thunderbolt sustained damage from enemy antiaircraft fire, and his disabled plane was seen to fall to the earth at a point approximately two miles northwest of the town of Lindau. It is regretted that no further information is available at headquarters relative to the whereabouts of your son.”

The family is still processing all the information that has poured in and the broad range of emotions it brings.

“(I’m) relieved to know what happened,” Jeanne said matter-of-factly Friday.

Jan and Tom Bradshaw continue to read all the information contained within the scrapbook, learning about a man they knew little about up until this year.

“His memory is so much more powerful now that we have stories,” Tom said.

“You wouldn’t think you would grieve,” Jan added, “but you do.”

A graveside service will be held 2:30 p.m. Friday at Tahoma National Cemetery in Kent. Tom Bradshaw will speak, but the majority of the service will feature military honors, including a potential flyover by the squadron he once flew with.

According to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, more than 400,000 of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II died. At the end of the war, 79,000 were unaccounted for. Today, that number is at about 73,000.

•••

Eric Schwartz is the editor of The Chronicle. He can be reached at eschwartz@chronline.com.