In short order, stickers with a rainbow shield and the words “Safe Place” will be popping up in businesses throughout Centralia. The city will be the newest member of the program started by the Seattle Police Department five years ago, which aims to help police and community members combat crimes of hate and bias.

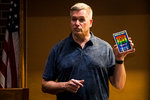

“I don’t have to tell you folks who live in small areas that things are often different,” said Jim Ritter, the founder of the Safe Place program and SPD’s LGBTQ liaison. “You’ve got large populations of LGBTQ folks and other minorities who may not be aware of where their police department stands on any of these issues. … This is going to have Centralia Police Department’s name on it.”

For Centralia Police Chief Carl Nielsen, joining the program was an important step in letting the LGBTQ community and other minorities know that law enforcement stands in their corner.

“Within the first 10 minutes (of learning about the program), I was sold,” he said. “There’s a need. The thing that sold me the best was that (Ritter) is getting phone calls up (in Seattle) from down here. If we don’t know an issue, we can’t resolve it.”

Thursday, half of the Centralia Police Department received a five-hour training from Ritter on LGBTQ relations and history. The other half will be trained Monday. From there, the department will administer the program with local businesses that want to get involved. To display the sticker, businesses must have their employees trained to call 911 when a crime victim enters their building and allow the victim to remain on-site until first responders arrive.

Ritter and Nielsen introduced the program Thursday evening to a group of about 20 community members at the Centralia Timberland Library. Knight Sur, conciliation specialist with the U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service, was also on hand to offer the services of his agency.

After creating the program in Seattle, Ritter found that minorities were far more likely to report hate crimes, knowing that law enforcement and the community had their back. In Seattle, 6,000 businesses now proudly display the sticker, and many police departments throughout the U.S. and Canada have joined the program.

“One of the reasons that victims of these crimes don’t report is become they’re not sure if anyone’s going to care,” Ritter said, expressing the importance of law enforcement of upholding its pledge. “When your name is on this, there has to be follow-through, there has to be a commitment. They’re going to test you on this. … I wouldn’t be here unless I thought your chief had a sincere desire to do this for all the right reasons.”

Nielsen has designated himself as the liaison for the Safe Place program, and he said that he expects any officer that responds to take it just as seriously.

“Contact me directly,” he said. “It may not be me who is responding, but I will get somebody out there for you. That’s how important this training is for us. … Bother us. We get paid, we work around the clock. That’s what we’re there for.”

In addition to the training, Safe Place also serves as a symbol to let minorities know they are welcome and let bigots know they’re being watched — and that harassment will not be tolerated.

“The symbolism on this thing is what’s really important. Not only do the victims see this symbol, but the suspects see this symbol,” Ritter said. “Criminals weigh the risks of doing things. If they think the heat’s being turned up on hate crimes because they’re seeing these signs going up, they’re no longer able to operate in obscurity. … They read it and they go, ‘Oh (expletive), what I’ve been doing here ain’t working anymore.’ And then we’ll send them back in the closet.”

Both Ritter and Nielsen emphasized the importance of calling 911, even if an incident might not rise to the level of a crime or a resident feels just generally uneasy about a situation.

“There’s nothing worse than being a cop or a police chief and not knowing what’s going on in your community, because it’s not being reported,” Ritter said. “We want to encourage officers to document anytime somebody feels threatened.”

Ritter, who served 11 years in his department before he felt comfortable coming out of the closet as a gay man, acknowledged that minorities might still have trouble trusting law enforcement. But he told the community members assembled Thursday that he had been pleased with the response of the Centralia Police Department, the vast majority of whom said they had LGBTQ people in their own lives. The officers were eager to ask questions and learn about the role they could play in Safe Place, he said.

“They ranged from veteran officers to officers that had only been here a short period of time,” he said. “There was no resistance, and I was thrilled to see that.”

Nielsen said he will be presenting the Safe Place initiative at the next city council meeting Tuesday, as well as the department’s upcoming community outreach events. He said he was eager to meet with local groups and area minority communities to discuss the program in a space that’s comfortable for them.

In addition to offering the program for Centralia businesses, Nielsen said it will help bolster the efforts of the department’s school resource officer, Mike Lowrey, to support LGBTQ youth.

Travis Pollanz, a Centralia business owner who helped start the conversation about bringing Safe Place into the city by emailing Ritter and city leaders, said members of the LGBTQ community need to step up and help give law enforcement a better sense of what’s going on in the community.

“We’re being provided with a great opportunity,” he said. “We have to do the work too. We can’t just expect the police to be mind-readers. … We have to come together. We have to figure out ways of participating with one another.”

Lewis County Cares, an LGBTQ network and resource group that Pollanz founded, will be part of that effort, he said. Even prior to Centralia’s implementation, Pollanz has had one of the Seattle Police Department’s Safe Place stickers in the window of his shop. It’s actually been good for business, he said, making it known to minorities that they will find a welcoming environment.

Centralia city council members Cameron McGee and Rebecca Staebler also attended the meeting, as well as employees from Centralia College and Timberland Regional Library. Staebler, herself a downtown business owner, said that the conversation started by the Safe Place program will extend beyond criminal matters, helping people learn how to respond to inappropriate comments.

Ritter added that with attitudes changing rapidly throughout the country, people are more open to participating than they were even five years ago.

“Everybody’s quiet until they realize learning about this isn’t going to hurt, and then they start chattering up a storm,” he said.

During the two-hour discussion, Nielsen made a point of asking community members about their own experiences, both with the community and his department. With the program in its “infancy,” Centralia leaders know they have much to learn, he said.

“We will make the time,” Nielsen said. “I will make the time.”

He added that he expects to other police departments, fire districts and the sheriff’s office will be clamoring to join the Safe Place program, once Centralia demonstrates its success. Ultimately, everyone assembled said they want to make the community a place where everyone feels comfortable being themselves.

“A community that has never had a voice in Centralia is getting a voice,” Ritter said. “You should be able to feel as comfortable holding hands down the street as anybody else.”