Centralia police officers gathered Monday for the second and final training session hitting on issues within the LGBTQ community and how law enforcement can effectively communicate with people in that community and investigate hate crimes.

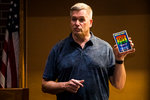

In the first hour of the training on Monday, Jim Ritter, LGBTQ liaison with the Seattle Police Department, asked officers if they have ever encountered a situation that directly involved members of the LGBTQ community.

One officer recounted an incident at a local bar, where a person was assaulted over their choice of gender-specific clothing.

Ritter asked the officer how he handled the incident. Just like any other, the cop replied.

More questions followed. Did you experience any specific anxiety while responding — maybe about how to properly address the person? Do you know much about pronoun usage? Not really, an officer answered

“OK, you’re going to learn about that later today,” Ritter replied, adding later: “The whole idea is to reduce everyone’s anxiety about working around people that you may not be used to working around.”

A lack of engagement with minority communities by law enforcement agency is often interpreted as indifference toward issues affecting those communities. If a crisis arises — such as a highly visible and widely reported hate crime — it’s difficult for an unengaged department to appear sympathetic in its aftermath, said Ritter. The public has a way of seeing through a prepared statement read at a press conference. An involved and engaged police department can dispel some of that mistrust before a crisis arises.

“If you don’t have a community outreach plan or mission, it leaves you at a significant disadvantage to defend against the allegations,” he said.

If law enforcement hiring standards hadn’t started to change in the late 1970s, Ritter’s career would have looked a lot different than it does now — if it started at all.

As an officer with decades of experience and as a gay man, Ritter said he has the unique experience of having a foot in two worlds that haven’t always coincided. Ritter recounted hearing homophobic comments and off-color jokes about sexual orientation on the job, before he felt comfortable coming out to his co-workers.

He discussed his hesitation to enter the law enforcement field as a young gay man, concerned about interviewing practices where an applicant was asked about his or her sexual orientation. Even in the 1980s, when such practices had been done away with, subtle questions — “What’s your wife’s name or girlfriend’s name?” — would sometimes force officers to out themselves.

That being said, Ritter said there’s a pro-police sentiment within the LGBTQ community. However, a general uncertainty about how a law enforcement agency might approach the often-sensitive nature of hate crimes against LGBTQ people may result in some trepidation about contacting officers.

For that reason, Ritter said, there’s value in police training and educating themselves on LGBTQ issues, so they’ll be well equipped to handle hate crimes with the appropriate care.

The training started around the time Ritter and Police Chief Carl Nielsen announced Centralia’s upcoming involvement in the Safe Place initiative, a program that allows businesses to be designated as a haven for hate crime victims and equips police officers with knowledge to handle the situation.

Nielsen, Monday afternoon as he introduced Ritter to the crowd of officers, asked the cops whom they work for.

“The community,” came the quick response. Nielsen assured that was the correct answer, and said it was community members that got the ball rolling on the training that day.

Nielsen, during a recent event at Centralia Timberland Library, said he was quick to move forward on implementing the Safe Place program and the training sessions.

“Within the first 10 minutes (of learning about the program), I was sold,” he said during the meeting last week. “There’s a need. The thing that sold me the best was that (Ritter) is getting phone calls up (in Seattle) from down here. If we don’t know an issue, we can’t resolve it.”

Ritter said he was in dialogue with Centralia business owner Travis Pollanz, who in turn contacted city officials and Nielsen about Safe Place. Nielsen contacted Ritter about bringing Safe Place to Centralia, and the chief now serves as liaison for the program.

Ritter, at the beginning of the four-hour training session, addressed how a constantly changing culture has improved conditions for LGBTQ officers. Ritter said the job wasn’t conducive to him coming out when he first started his career as a sheriff’s office deputy and later as a Seattle Police Officer in the 1980s.

Now, he serves as a full-time LGBTQ liaison for the Seattle Police Department — one of the only departments in the country to have a full-time employee dedicated to bridging the gap between police and the LGBTQ community.

Ritter asked the officers Monday if they’ve ever had a conversation with a community member that turned into a more significant dialogue.

A number of officers said that they did, and one saying that he’s spoken with people in the Hispanic community about his own background and Hispanic heritage. Ritter responded saying that such conversations with minority communities do more good than a planned community meeting ever will.

“I’m convinced that most minority folks that you know, if they think you’re asking for the right reason, will be more than happy to talk to you about their lives. Now, obviously you don’t want to go out on calls and start getting in people’s personal lives, but you’re a good reader of people,” he said.

He had the officers then engage in an exercise to both expose and open the conversation on stereotypes. He split the room up into four groups. One he had write a number of positive stereotypes about police officers. Another, he had write down negative stereotypes about officers. The third, he had write about positive stereotypes about the LGBTQ community, and the last he had write negative stereotypes about the same community.

Going around the room, he encouraged the group writing negatively about the LGBTQ community to feel free to use whatever words come to mind. He won’t be offended, he said, and ensured he talked to Nielsen about the exercise — they weren’t going to get into trouble.

Each group had a long list of words and phrases — some saying that cops are perceived as racist, others that cops are perceived as community servants and others that the LGBTQ community is perceived as progressive and prone to community activism.

The other group had a list of slurs and misconceptions often directed at LGBTQ people. Ritter said the exercise was to both dispel myths about certain stereotypes and to put them in the shoes of people who might be at the receiving end of slurs — he said to imagine being in school, and have some of those words thrown at you.

“You’re not going to learn everything about LGBTQ today, and I’m OK with that. At 58 years old, I’m still learning about this community. Because what happens? It changes. Words change, dynamics change. It’s a constant learning process,” he said.

At the end of the first hour of the session they took a break. Ritter said during the rest of the time, they would cover topics with the intention of getting a “dialogue going to a degree that it’s never been before.”

“When these officers leave this training, they will have a better understanding of the LGBTQ community, the community’s challenges with police through history and the direction that they’re going from this point on,” he said.