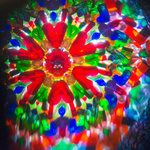

William Tate loves his kaleidoscopes.

He sometimes sits for half an hour looking through the viewfinder. He said he finds the images soothing and noted that many therapists keep kaleidoscopes in their waiting rooms for clients to use for relaxation.

“You’ll never get the same picture twice,” he said.

But just like the ever changing pictures in the kaleidoscope viewfinder, calling Tate a kaleidoscope-maker would be too limiting. Take a tour of the Rochester home he shares with Sharon Hatch and you’ll quickly notice arts and crafts are a constant part of their lives.

Tate was born in Oklahoma and later moved to California where he attended high school and college. After college he worked for various phone companies in jobs that took him to many locations. He and Hatch met more than a dozen years ago. The two lived at the same park for the elderly and they met when he bought a golf cart from her. They decided to have dinner together and discovered they had a lot of things in common, including their love of crafting. On their first date, Hatch had a baby quilt to finish and Tate offered to help iron the pieces for her.

“That’s what brought us together was her desire for crafts,” he said. “I knew we would get along just fine.”

Tate said he remembers always enjoying making things with his hands. He still has a wooden chess board he built in high school shop class in 1962 (more recently he completed the chess pieces to go with the board). But during his working life he had not really been involved with woodworking until 2002 when he joined Hatch on her annual winter stay in Arizona. The clubhouse at the community in which they stayed had a wood shop and William befriended many of the men there and they all worked on projects together.

The couple settled in Washington 12 years ago because Hatch is originally from the state and has grown children here. She was born in Wenatchee and then lived in Seattle from the age of 7 on.

Once Tate’s love of woodworking was sparked, he said it was hard to turn it off. Among the many items he has crafted, on display in their home are: a working spinning wheel; wooden pens and styluses; and the urn that will someday house his ashes. He has also built various items for Hatch including: a fabric cutting table; a thread holder; and a display case for her ceramic bird collection.

He said he makes some of his creations from patterns and others are his own design, such as his walking stick that comes apart for easy travel and includes a compass but also doubles as a camera monopod.

“That was a need, really,” he explained.

“You don’t really need everything you make,” Hatch added. “Sometimes you just want it. You can it for the challenge.”

Tate got started in making kaleidoscopes about four years ago when he was a member of a wood turning club in the Olympia area. One of the men he met through that club is an expert kaleidoscope-maker and agreed to show him his technique. The couple also traveled to Brookings, Oregon where Tate visited and learned from a professional kaleidoscope manufacturer.

Most of his kaleidoscope designs begin with a “sandwich” of different layers of hardwoods that are turned on a lathe to create a patterned outside. But it is the mirrors on the inside of the shell that are the hardest thing about making a kaleidoscope. You must use just the right kind of mirror or the light will not reflect correctly. The pieces must be meticulously cut to a precise shape and size. When you cut them, putting too much pressure will cause chips that will be visible in the finished products — too little pressure and it will not break in the correct place. Once cut, they must be almost immediately secured to each other at just the right angle. When asked if he’s ever had a kaleidoscope not turn out, he laughed and pointed to a half-full box of rejected mirror pieces.

“This has been quite a learning curve for me, I can tell you,” he said.

Many of Tate’s first kaleidoscopes featured beads but he said the real collectors actually look for “glass works,” pieces of hand-shaped colored glass. Tate said he is working on trying to make his own glass works to get the finished pieces just right.

Some of his kaleidoscopes are about the size of a kaleidoscope one might find at a toy store. Others are larger kaleidoscopes and sit on a base lit by LED lights. He said some of his largest pieces can take up to 100 hours to build.

But woodworking is not the only craft in which the couple excels. They both do 3D paper tole, stained glass, lapidary and Hutch creates intricate beaded designs. They also quilt together, she pieces and he quilts the finished product. In fact, one of his newest challenges is quilting using a state-of-the-art robot quilting machine he just purchased. The couple quilts many quilts for the “Stitch ‘n Peace” group in Rochester, which makes quilts for a variety of local charities including those helping: veterans; expectant mothers; and those who are homeless. Last year the group made and donated 200 quilts.

William experienced a mild stroke about a year ago. He said at first it was very much in question how much of his crafting he would be able to return to. But through therapy he has been able to return to his loves.

“The main thing, of course, was being able to pin the quilts on the frame,” he said with a smile.